The Tale of the Eternal Packet

All of us went through that early on network training and heard about loops and how they can cripple a network. Depending on when you got your start in networking, you were then told that you’re not likely to see those types of problems due to Spanning Tree or other network improvements since back in the day. Well, every once in a while, if you try really hard, you can still come across a good ole loop to give you a run for your money. This wasn’t my first instance, but hopefully it will be my last. So, this is the tale of the eternal packet, or should I say an eternal packet.. May it hopefully help some weary Googler in the future.

The year was 2017 and it was a rainy Tuesday morning working on setting up a new Disaster Recovery datacenter. There had been some intermittent issues on the VPN gateways that didn’t seem consistent at all. We identified that the CPU was running near 100% at all times unless it was shortly after a failover or reload. But, without fail, it would creep itself back up to 100% utilization as we did VPN testing. The VPN firewalls were a pair of ASA 5585 SSP-10s and we were testing with 1-3 users at any given time, so it was obviously quite amazing that it was having this serious of a toll.

------------------show cpu usage ------------------

CPU utilization for 5 seconds = 99%; 1 minute: 99%; 5 minutes: 99%

------------------ show cpu detailed ------------------

Break down of per-core data path versus control point cpu usage:

Core 5 sec 1 min 5 min

Core 0 98.8 (93.6 + 5.2) 98.7 (94.1 + 4.6) 98.7 (94.2 + 4.5)

Core 1 99.8 (99.8 + 0.0) 99.7 (99.7 + 0.0) 99.8 (99.8 + 0.0)

Core 2 98.6 (93.4 + 5.2) 98.7 (94.1 + 4.5) 98.7 (94.2 + 4.4)

Core 3 99.6 (99.6 + 0.0) 99.8 (99.8 + 0.0) 99.8 (99.8 + 0.0)

------------------ show process cpu-usage sorted non-zero ------------------

PC Thread 5Sec 1Min 5Min Process

- - 25.0% 25.0% 25.0% DATAPATH-1-1822

- - 25.0% 25.0% 25.0% DATAPATH-3-1824

- - 23.4% 23.6% 23.6% DATAPATH-0-1821

- - 23.4% 23.6% 23.6% DATAPATH-2-1823

0x00007f6d80d38359 0x00007f6d60296fc0 2.1% 2.1% 2.1% CP Processing

0x00007f6d822e400b 0x00007f6d601d7500 0.4% 0.1% 0.0% ssh

0x00007f6d82e05e2f 0x00007f6d6029b840 0.1% 0.1% 0.1% bcmCNTR.

As you can see, the DATAPATH-#-#### threads are all taking up nearly 25% of total CPU resources. Given it is a quad core CPU, that means they’re using nearly all CPU cycles in total. There are actually a handful of bugs regarding those threads taking up a of the CPU or causing a crash, so I worked through some of those at first. I downgraded to another code version which seemed to take care of the problem, but given it was just been tested by a single person, it didn’t really test it thoroughly enough. Once this came back to be a problem, it presented the same way – users connecting to VPN would connect slowly, and often times authentications would time out preventing successful logons. This was all a symptom of the hogged CPU.

Upon further inspection, the inside interface was showing an incredible amount of traffic throughput. Keep in mind that at this time, there was only a few of us that were testing on this firewall.

------------------ show traffic ------------------

inside:

received (in 590906.900 secs):

194253969761 packets 15095372560634 bytes

328004 pkts/sec 25546000 bytes/sec

transmitted (in 590906.900 secs):

194262351340 packets 15104470809003 bytes

328004 pkts/sec 25561005 bytes/sec

1 minute input rate 361141 pkts/sec, 24074337 bytes/sec

1 minute output rate 361140 pkts/sec, 24074091 bytes/sec

1 minute drop rate, 0 pkts/sec

5 minute input rate 355476 pkts/sec, 23687711 bytes/sec

5 minute output rate 355476 pkts/sec, 23687331 bytes/sec

5 minute drop rate, 0 pkts/sec

Yep, that’s about 24GB per second over the course of one minute and five minute sampling windows (as well as the 590906 second window - about 6.8 days). That’s a whole lot of data for a firewall that’s not in any real traffic path besides for VPN users which there are a couple of that aren’t using it for any extended period of time. I took a look at the connections that the firewall had established, and there was a ton of traffic go to or from IP addresses that were part of our VPN address pool ranges. (Unfortunately, I don’t have the show connoutput saved). Here’s the kicker, though, they weren’t actually connected anymore. So, here we are looking at a bunch of ghost addresses generated an enormous amount of traffic somehow.

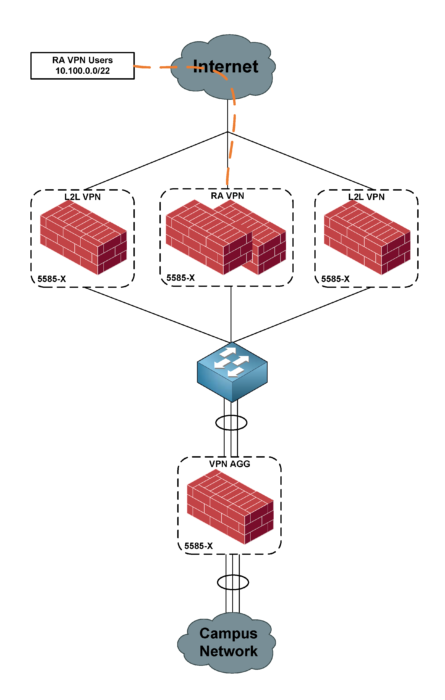

The key to answering this question lies in the design of the network surrounding the firewall having the issues. We have what I would call a “VPN Enclave” in this scenario. We have the requirement for a few firewalls to terminate site to site VPNs and then a pair for remote access VPNs (which is the firewall having CPU issues). Behind these firewalls sit yet another firewall that acts as an aggregator for the VPN firewalls in order to simplify management, as well as because the other firewalls could be managed externally and the aggregate gives a single point of single-owned management. This may be overkill, but let’s not talk about that here, as this is a “the powers that be have spoken” kind of situation.

The problem ultimately was due to a routing loop that occurred when traffic was destined for an IP address of a VPN client that is no longer connected. When a VPN client connects, the assigned IP address gets injected as a static /32 route into the routing table. The following output shows this (as these are not configured static routes):

VPNFW/act/pri# show route | i 10.100

S 10.100.0.10 255.255.255.255 [1/0] via 22.22.22.1, outside

S 10.100.0.11 255.255.255.255 [1/0] via 22.22.22.1, outside

When the clients were connected, the routing would look like this:

The VPN pools were not explicitly specified to route outside via a static route, and when they are connected this isn’t a problem as the longest prefix match (the /32) would be used. Otherwise, the 10.0.0.0/8 inside route would be preferred as it envelopes the default route. With no VPN routes connected, routing would look like this:

Of course, you’re probably thinking, “What’s the big deal? Disconnected clients obviously don’t send traffic..” Well, right you are; however, apparently these clients would send a steady stream of NetBIOS, amongst other things, that would fire off right before disconnecting. So, the RAVPN firewall would route the traffic inside towards datacenter/campus resources. The aggregate firewall would then route the return traffic outside to the RAVPN firewall for VPN subnets, but now the client is disconnected and the RAVPN firewall would look at its routing table and match the inside supernet because the originating client is, despite originally having a route injected for the outside by the VPN process, is no longer connected. This would route the traffic back to the aggregate firewall. It would, of course, route it right back.

Now, this may not normally be a problem because eventually the packet will bounce around the network and the TTL will expire and it won’t have that much of an impact. This case, however, was a great reminder of the fact that firewalls do not decrement the TTL of a packet when passing it through. Given that the devices that were bouncing the packet back and forth were two firewalls connected via an L2 segment, the TTL never decremented and resulted in an eternal packet.

The lesson here – long story short – is to hard code static routes for your VPN pool subnets to go out of the outside interface. This will prevent any inclusive supernets routing out of other interfaces from wreaking havoc like in my situation. The concluding routing would look like this, with a “floating static route” of sorts to catch the VPN traffic when some of that lingering traffic is returning.

You may be using VPN pools that aren’t from your inside network’s ranges, and that would prevent something like this from happening as long as the default outside route catches the traffic. As a rule of thumb, though, always remember to hardcode that static route, as it is generally a good thing to do to prevent unforeseen issues.. especially in this situation.